Author's Introduction

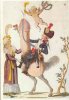

Later today, I will begin posting my newest story, “Rebecca and the Bloody Codes.” This is a story (and girl) that I have played with in my mind for a long time. I hope it appeals to my readers.

I enter into this project with trepidation when I think of the seriously great authors who have covered (either directly or indirectly) this era and topic before.

The year before the action happens in my story, in 1722, Daniel Defoe, fresh from the runaway success of Robinson Crusoe, published The Fortunes and Misfortunes of Moll Flanders, the story of a women, born in Newgate prison to young woman about to be hanged for petty theft. Pleading her “belly,” the execution is postponed and she is later transported to the Virginia colony leaving Moll to be raised from the age of three until adolescence by a kindly foster mother. Thereupon, she sets forth on a life of lusty adventures. Not really pornography, but a romping good read. BTW – there are some questions as to whether Defoe really wrote it – his name did not appear on any edition until decades after his death.

In 1749, two decades after my story, Henry Fielding published The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling, generally considered the first English prose work to be considered a novel. Samuel Taylor Coleridge argued that it has one of the "three most perfect plots ever planned." It became a bestseller, with four editions being published in its first year alone. I presume most readers are familiar from one of the movies or TV adaptations. I read the book in my misspent youth, though, in this time of benighted education and devil-inspired tweeting, few will have read its 346,747 words.

Most significant of all, is the work which leaves my humble efforts to grovel in the mud, Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (popularly known by the protagonist’s name Fanny Hill), published by John Cleland in 1748. It is considered the first original English prose pornography, and the first pornography to use the form of the novel. It is one of the most prosecuted and banned books in history. Surprisingly, though clearly pornographic, it never uses any anatomical or “dirty” words for parts or actions. A substantial part of the humor and entertainment of the book comes from a plethora of inventive euphemisms (the vagina, for example, is often referred to as the “nethermouth.”).

With these and other quality writing to choose from, my readers would be well advised to leave now and seek better entertainment.

For those foolish enough to remain, this story will move slowly, I am trying, more than usual to give a feeling and experience of early 18th century London. There will be [trigger warning] extensive non-consensual sex, some sex cum punishment, a possible prison whipping, and always (courtesy of the “Blood Codes”) the ominous threat of a hanging for an innocent young woman.

I have, as of this moment written about one third of the book. Even I do not know how it ends.