I posted this in my crucifixion story, Goth Girl (

https://www.cruxforums.com/xf/threads/the-fate-of-a-goth-girl.8750/page-22#post-604092). It seems worthwhile posting here.

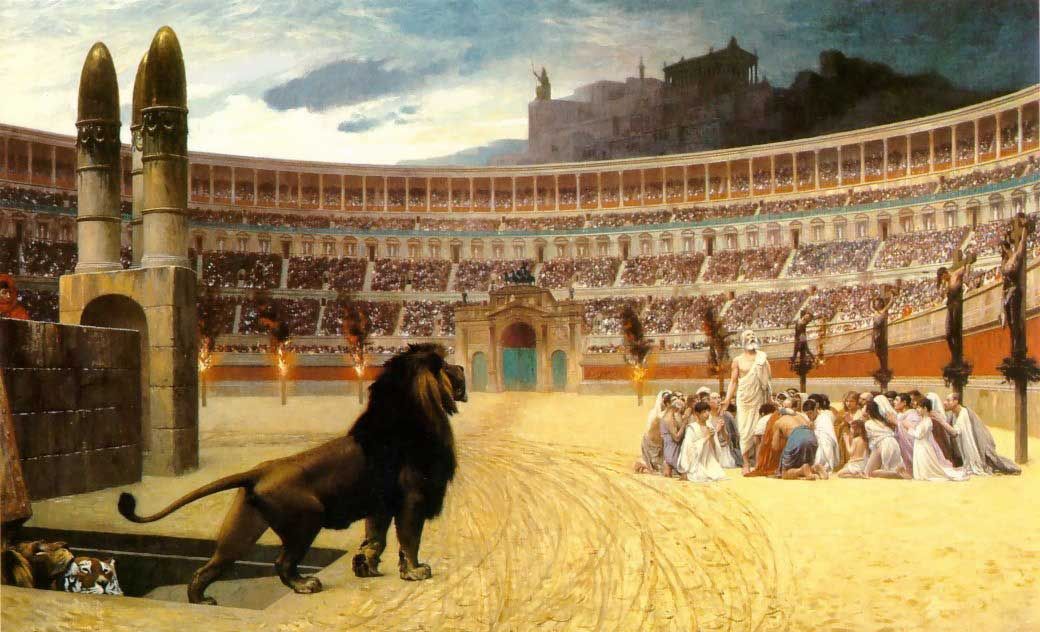

When we think of the Roman Empire, visions of brutal conquest, enslavement, tyrannical Emperors, and rule by intimidation (such as the always popular flagellation and crucifixion) come to mind. And, indeed all of these happened. But, if we focus on just these, we miss a truly remarkable development in government and nationality that first occurred under Roman rule.

Roman citizenship was a legal concept carrying significant rights. Originally this was reserved for the Romans who lived in Rome and the nearby countryside. Soon, growth forced the granting of “Latin Rights,” a kind of junior citizenship, to the inhabitants of Latium, the region immediately surrounding Rome. In the 90s BC, there were the “Social Wars," in which Rome’s allies in Italy (social came from

socii or allies) revolted and to end the conflict, Rome passed the

Lex Iulia de Civitate Latinis Danda in 90 BC, granted the rights of the

civitas Romanum to all allied states in Italy except the Gauls in Northern Italy.

After this, the granting of citizenship was used as a way to bind new conquests to Rome. It was a powerful boast of the Apostle Paul when he said to the Roman officer who was about to have him flogged, "

Civis romanus sum (I am a Roman citizen)."

In the early 2nd century BC, the

Porcian Laws guaranteed a citizen the right to appear before a proper court and to defend oneself, the right to appeal from the decisions of magistrates and to appeal the lower court decisions; they could not be tortured or whipped and could commute sentences of death to voluntary exile unless found guilty of treason. If accused of treason, a Roman citizen had the right to be tried in Rome, and even if sentenced to death, no Roman citizen could be sentenced to die on the cross.

In 212 AD, the Edict of Caracalla (officially the

Constitutio Antoniniana) declared that all free men in the Roman Empire were to be given full Roman citizenship and all free women in the Empire were given the same rights as Roman women.

It is perhaps difficult for us today to understand the depth of this change in policy. Previous concepts of ethnicity and nationality would never have conceived of such a thing.

In 383 AD, in our story, virtually everyone but slaves and the newly arrived Goths were Roman citizens and felt a part of the Roman Empire. While I have identified some ethnic backgrounds to help your understanding of the characters, they all (with the mentioned exceptions) would have regarded themselves as Romans, citizens of that ancient city, and of the sprawling Empire that ringed the entire Mediterranean.

www.theguardian.com

www.theguardian.com